Many organizations using GitLab want to understand how to best apply the various features to support Agile project and portfolio management processes (PPM) at scale. These organizations use different Agile frameworks. In a previous blog post, we outlined an approach for using GitLab for Agile software development. Since the original post, we've continued to enhance functionality for lean/Agile portfolio planning and Agile project management. In this blog post, we’re updating recommendations for using Agile based on these enhancements and we describe how these features can be utilized for a variety of different scaling frameworks.

Agile software development at scale

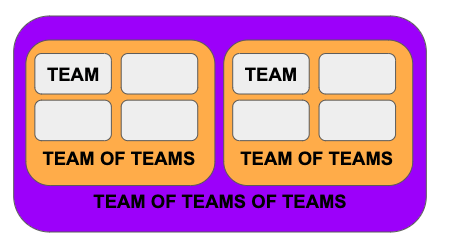

First, let’s take a look at a typical scaling model of Agile software development beyond the individual team level. Whether you’ve adopted a specific scaling framework such as the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe), Disciplined Agile (DA), Large Scale Scrum (LeSS), or Spotify, most scaling models have similarities in their approach, organizing Agile teams into teams of teams, and even into teams of teams of teams.

Typically, scaling frameworks use these types of labels to describe each level:

| Level | Common Names | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Team | Scrum team, Kanban team, Squad | A cross functional group (including BA, Dev, Test, and other supporting roles) implementing stories and bug fixes for an application or set of applications |

| Team of Teams | Program, Release Train, Tribe | A set of teams who plan together and coordinate efforts to implement features for a system involving one or more applications |

| Team of Teams of Teams | Portfolio, Business Unit, Alliance | One or more programs with a shared set of strategic goals and themes, typically funded with a single budget |

Now that we've reviewed the different levels of Agile at scale, let’s next think about what types of data and visibility are required for agility at each level.

The scrum master/project manager/tribe lead, product owner, and team members are part of the Team level that is focused on short-term planning, typically weekly to monthly. They will want:

- A board view to show flow of work

- Current and upcoming iteration plan

- A task list for each work item

- Visibility into team progress

- Team predictability

The program manager/release train engineer, product manager/product area lead, and design lead guide the Team of Teams, with a focus is on mid-range planning, monthly to quarterly (or potentially a bit longer). They will want visibility into:

- A prioritized feature list with anticipated business value captured

- Feature roadmap

- View of mid-range plan

- Epic health

- Progress against plan

- Program predictability

Finally, portfolio managers, business leaders, and chief architects perform strategic long-term planning, typically quarterly to annually or longer, at the Team of Teams of Teams level. They will want to see:

- A list of long-term epics/initiatives/business projects, categorized by theme and/or strategic goals

- The long-term strategic roadmap

How can we best support these needs using GitLab?

First, we need to understand what GitLab object types to use for support the appropriate visibility at each level.

| GitLab Structure | Team | Team of Teams | Team of Teams of Teams |

|---|---|---|---|

| Org structure | Project or sub-sub-group | Sub-group | Top level group |

| Work items | Issue | Child epic | Parent epic |

| Time boxes | Iteration | Milestone | Roadmap across milestones |

In GitLab, epics can be defined in a hierarchy to break down long-term epics into a set of shorter-term epics that can each be delivered by a single Team-of-Teams. While we will use a single parent-child epic hierarchy in this blog to keep things simple, you can use more levels of nesting. The lowest level of epic in the hierarchy would be linked to a set of issues to define the work each team will do in order to implement that epic. GitLab is very flexible and does not enforce a hierarchy. For example, when there are cases when an epic should be tracked at the portfolio level but be decomposed directly into issues, with no features in between, GitLab will allow you to do that linking directly without having to create dummy features in the middle.

We recommend using scoped labels to define epic types, e.g., you might define long-term epics to be portfolio epics, and decompose them into shorter-term features. Using epic::portfolio-epic and epic::feature will allow you to appropriately categorize and filter a list of epics and make sure that each epic exists in the appropriate location.

A group can be used to organize projects. And groups can be nested, e.g., a parent group can contain multiple child groups, and each child group can have its own subgroups, etc. A GitLab project contains a single source code repository, issue tracker, and associated tools and functionality in order to collaborate on software development for that repository.

Note: Group permissions are propagated down the tree from the top-level, so, e.g., a maintainer in the top-level group will have maintainer permissions in the entire group hierarchy.

We recommend that you use a nested group hierarchy to define your scaled organizational structure for Team of Teams of Teams, Team of Teams, and Teams. For example, consider an electronic banking program that is part of the digital services portfolio for a financial services provider. The electronic banking program might have separate teams that work on web, mobile, backend, and middleware. You would use a parent group for the digital services portfolio, a sub-group for the electronic banking program, and a separate project within the sub-group for each team.

Generally speaking, parent epics would be defined within the top-level group since they define work that can span the sub-groups. Each parent epic would be broken down into multiple child epics, each of which is defined within the appropriate child group (representing a Team-of-Teams).

The example above is simple in that each Agile team is working on a single repository. But what if that’s not the case?

- If a single team works exclusively on multiple repositories (but no other team works on the them), then create a sub-group for the team, and include each repo as a project.

- If multiple teams work on a collection of repositories, use the Team of Teams group for collaboration across all Teams in all projects, and use individual scoped labels for each team to track their issues on filtered boards.

GitLab provides an issue tracker for any types of issues you want to manage and track. Typically, for Agile software development teams, these would be things like user stories and defects. We recommend that you use scoped labels to define the different issue types, for ease of filtering and reporting. The great news is that you can have as many or as few issue types as you see fit. GitLab does not provide the ability to define a custom schema for each issue type as that tends to complicate both administration and usage of issues and gets in the way of software development. Instead, use custom issue templates to provide guidance to the end user on what types of information should be captured for each issue type, and even to set labels automatically on the issue as it is created.

GitLab makes project status reporting easy with the issue health status. Each issue can have a status of On Track, Needs Attention, or At Risk. The health statuses of all issues for an epic are reported within the epic details for a quick snapshot of the health of the overall epic.

Finally, we have to define timeboxes to use for our planning cadences. We tend to use milestones for our mid-range planning, i.e., a quarterly development plan. Define the milestone at the highest group level that will be using that cadence, e.g., if the entire portfolio plans on a quarterly basis, then the planning milestone should be defined at the top-level group level. If each team of teams plans on a different mid-range cadence, then you would want to define separate milestones at each child group level. Note that milestones get added directly to issues, so the projects that will use the milestones must be within the group hierarchy where the milestone is defined. One other consideration is that an issue can only have a single milestone associated with it, so it’s a good idea to align on the best use of milestones across the Team of Teams before starting to use them.

We recently released our iterations MVC in GitLab! This allows you to define, at the group or individual project level, short-term cadences that a team or set of teams uses for planning and tracking their work. While, as an MVC, iteration functionality is not yet as robust as milestones, we do have plans for enhancements including using iterations on boards, filtering issue lists by iteration, and burnup/burndown charts. You can view the epic Iterations in GitLab to learn more about planned enhancements. And that doesn’t mean Kanban teams are out of luck. We innately support Kanban in GitLab, too, with issue boards, so you can have a mix of iteration based teams and continuous flow teams working together.

Agile PPM: putting it all together

Here’s how the GitLab features come together to support Agile at scale to allow planning from the highest level down to the individual team, and to provide visibility, traceability, and reporting at each level:

You can also check out the video below to see how the structure comes together in GitLab.

Read more about Agile at GitLab

- See more information about our Agile delivery solution

- Build your Agile roadmap in GitLab

- Learn how to create iterations

Cover image by Martin Sanchez on Unsplash